Circular economy and the EU

Rising temperatures, the loss of biodiversity, the plastic soup, and the limited availability of resources are four problems all European countries are facing at the moment. The occurrence of these problems has been a motivation for the European Union to start looking for a solution. Circular economy is nowadays considered to be the most feasible one. Whereas the contemporary linear economy is based on the ‘fast turnover’ principle, which stimulates people to buy new gadgets, clothes, and furniture at a high frequency, the circular one aims to minimize waste by making products last. The goal is using and reusing, not using up. Many governmental organizations see the circular economy as the future business model and celebrate it for many reasons: it could bring a 70 % cut in carbon emissions by 2030, and play a key role in fighting food waste and reducing the amount of plastic soup. One might almost think that circular economy is a magical fix that is going to solve all our environmental problems.

Too good to be true?

The word ‘almost’ is key in the last sentence. While there are indeed many visions of realizing a utopian world by means of the circular economy, the reality is much harsher. Our contemporary way of thinking, our dominant habits, and our shared norms and values are largely based on a taking-making-throwing-away mentality. Most Europeans want to have the newest gadgets or the latest fashion. If our phone’s battery dies, we buy a new phone. Despite several initiatives of the European Union and the national European governments, the number of circular business models in Europe is still very low. More importantly, many circular initiatives run aground.

Circular economy defined

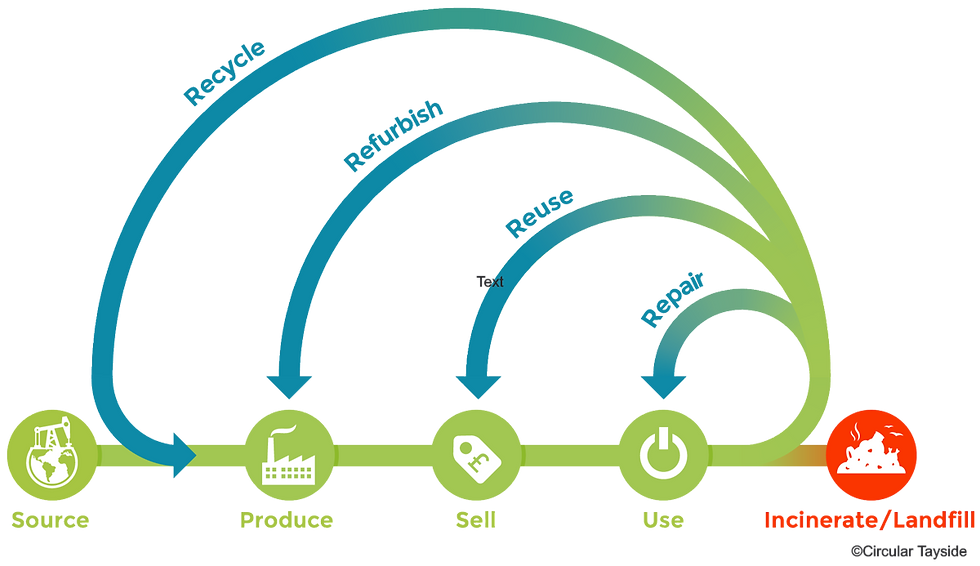

A major part of the difficulty of establishing a transition towards a circular economic model stems from limited understanding of the way the circular economy works. To decrease the economy’s impact on the environmental system, the aim is to reduce the input of primary resources and the output of waste by using feedback loops (as can be seen in the figure below). It is important to keep in mind that these feedback loops should be energy efficient. The basic elements of the circular economy, repairing, reuse, renovating, and recycling, require energy. In general, one can assume that reusing and repairing are relatively energy-efficient feedback loops, whereas recycling and renovating cost more energy. So, the smaller the loop in the picture below, the more circular. If one aims to be fully circular, this could lead to unsustainable levels of energy consumption because in each circular flow little amounts of materials will leak out. The tracking, finding and recovering of these leaked resources would be a journey without end and would cost a disproportionate amount of energy.

Meanwhile in the EU

Unfortunately, many governments and organizations see the circular economy as a recycling issue. As long as used products do not end up as waste, all is good. In fact, the circular economy requires another approach. Producers should already think about how products can be repaired, reused or refurbished during the design process. Up to now, such considerations have been neglected. New directives of the European Union will, however, force companies to also take reparability, upgradability, durability, and energy efficiency into account. For instance, one directive states that batteries should from now on always be replaceable. In such a way, consumers do not have to throw away their phone as soon as the battery dies.

Another example of a directive is the extended producer responsibility for many products, which means that producers are responsible for the recycling process after a consumer decides to not use their product anymore. The idea is that producers will be forced to also think about the way products can be recycled in the design phase.

What about the consumers?

The successfulness of such attempts will largely depend on the reaction of consumers. If we can repair our phones more easily, but we are not willing to do so, no law will be able to force companies to behave in a more circular way. So, for the circular economy to be effective, a change in consumer behaviour is crucial. As long as consumers prefer cheap and short-lived products over more expensive durables, the new directives are unlikely to have a positive effect on the European economy’s level of circularity. In a recent Eurobarometer consumers were asked about their most important considerations when buying new products. Price was seen as more important than the product’s impact on the environment. Furthermore, respondents believed that recycling was a better way to reduce the economy’s impact on the environment than buying products made by eco-friendly manufacturing. These results indicate that there is still a long way to go.