#Infodemic: assessing trustworthiness of COVID-19 news on Twitter

- Vittorio Vergano

- Mar 29, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2020

In February, the World Health Organization made common the use of the term infodemic in newspapers and journals. This expression describes the malevolent effect of a pervasive spread of information; in this context, it is referring to the excessive diffusion of content concerning coronavirus.

It would be quite a cliché to talk about the high level of connectivity to which we are used to in the 21st century, and it is also becoming quite mainstream to talk about the damage provoked by the surplus of information.

However, it is important to stress that the rapid circulation of news, combined with the common misconception that opinions and facts are the same, gives rise to the phenomenon of fake news and hoaxes propagating in traditional media formats.

The objective of this article isn’t to talk about such phenomenon per se; rather it aims to describe with few numbers the dramatic COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and the parallel infodemic which formed subsequently, allowing fake news to spread deliberately and pollute the already overloaded information system.

The dataset

The analysis was executed on a dataset

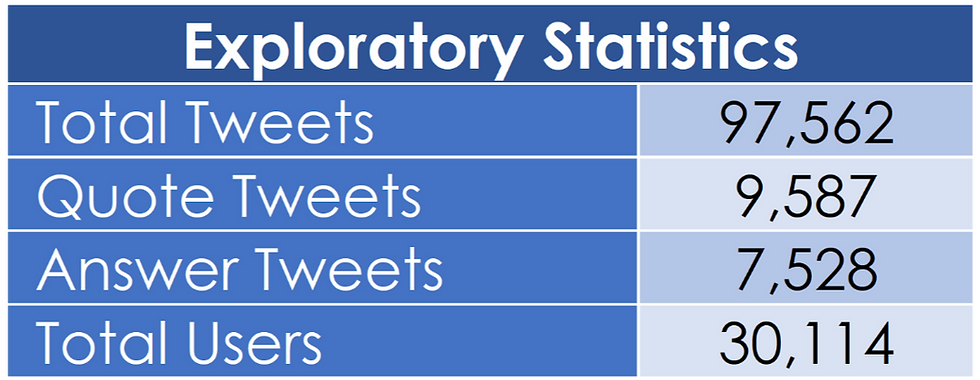

composed of almost 100,000 Italian tweets containing the hashtag #Coronavirus or #Covid-19 collected between the 6th and the 15th of March 2020; the main events in this time range were the announcement of the Lombardy region lockdown on the 9th March and the enforcement of the national “I stay at home” decree on the following day. Retweets and tweets containing a media (gif, image, or video) were ignored to avoid redundancy and to ease the analysis. Approximately 10% of the tweets are quoting other tweets and roughly 8% of them were replies to another tweet.

An assessment of tweet reliability

The first objective of this project was to discern between reliable and unreliable tweets. The model used for this classification problem was a simple logistic regression, which achieved a good level of efficiency as shown in the table. The tweets were split into reliable ones and unreliable ones. In this analysis, unreliable refers to tweets containing unverified or false information, clickbait and conspiracy theories. The model was trained on approximately 1,500 tweets that were tagged manually specifically for this project. The sources used to verify the truthfulness of the news were the website of ANSA – the leading news agency service in Italy – and Bufale.net – a well-known Italian fact-checking website.

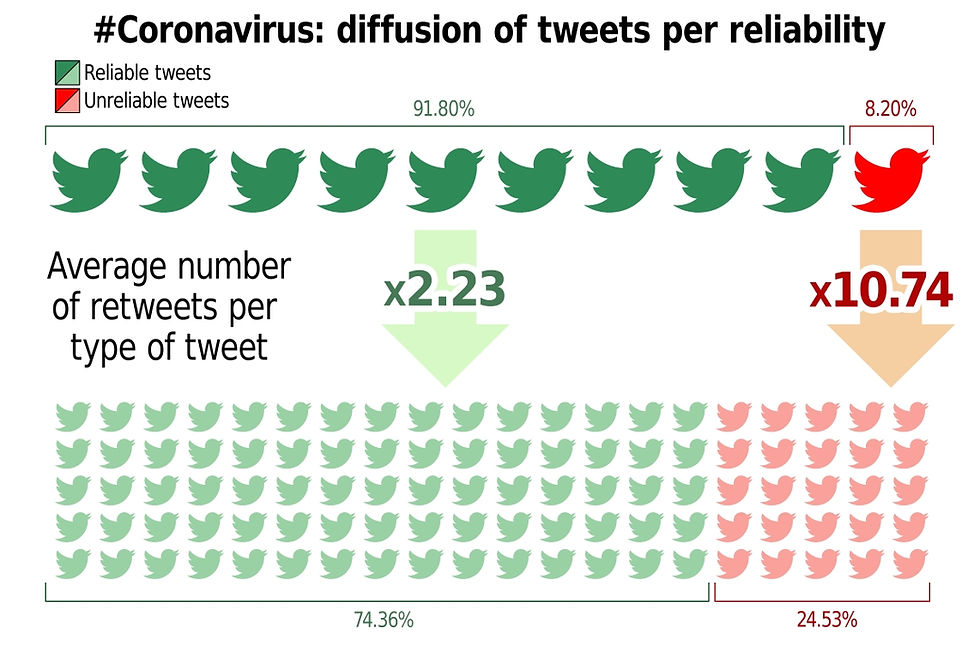

Out of the all analysed tweets, approximately 11% were considered unreliable. This result however was not satisfactory for two reasons: first, the main aim of the analysis was to check the diffusion of fake news among people, but many tweets in this sample were authored by trustworthy newspapers and news agencies – e.g. @LaStampa or @Corriere. In addition, the model discernment was made on the base of a probability (i.e. a given tweet is reliable with a probability X or unreliable with a probability 1-X); hence the more ambiguous results were classified as reliable or not on the basis of a slight difference in probabilities (the most extreme example would be a post with a 51% chance of being reliable against a 49% chance of being unreliable). For these reasons, a probability threshold of 75% was set and the main editorial authors were removed. The restricted sample, which will be used in the rest of the analysis, resulted in 48,882 tweets. Out of these tweets, 8% was classified as unreliable.

Although these figures seem reassuring, the fact that the data collected was filtered for retweets should not be ignored. In fact, fake news propagates more than reliable news; actually, it should be noted that the average number of retweets of unreliable tweets was almost five times higher than that of reliable ones (10.74 against 2.23). Multiplying the results previously obtained by the respective average retweet rates +1, the total number of reliable and unreliable tweets (including retweets) was obtained. These new results are not as encouraging as the previous ones: approximately 25% of the Italian tweets concerning the coronavirus posted between the 6th and the 15th of March were unreliable.

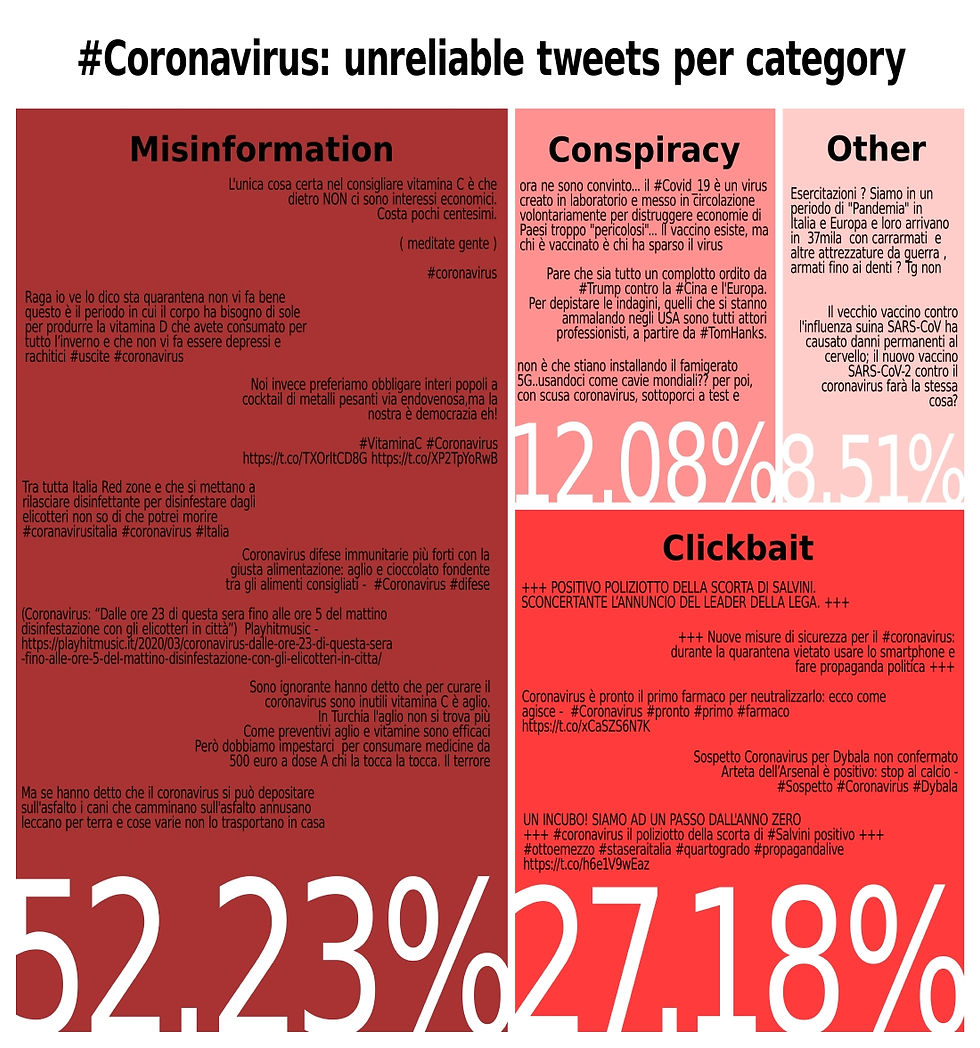

A further division was done among the unreliable tweets. At this stage, they were classified in four different categories depending on their content: misinformation (M), clickbait (Cl), conspiracy (Co) and other (O). The model used in this case was a Random Forest which obtained a discrete overall accuracy.

The graph below represents the distribution of unreliable tweets across the above mentioned classes. It appears that roughly half of the tweets fell into the misinformation category: they are either misinformative (information that is unintentionally incorrect or misleading) or disinformative (spread false information deliberately). The most important topics discussed in the tweets of this category were alternative methods to fight and beat the virus (e.g. homeopathy, vitamin C, garlic), the sudden discovery of a miraculous cure, channels of infection which have been disproved by experts, and fake news concerning celebrities and football players.

Approximately one quarter of the inspected tweets were clickbaits, namely, they consisted in catchy titles or article headers inducing people to click on a link with misleading information.

Finally, 12% of the tweets discussed conspiracies such as the creation of the virus in a laboratory, the use of 5G mobile networks to spread the virus and control the population, or the American tanks and troops coming to invade a weakened Europe. Given the feeble difference between the features presented in these three groups, the other category was created to cluster tweets that presented features of more than one of the groups (e.g. a misinformative clickbait).

Diving into the literal content of coronavirus tweets

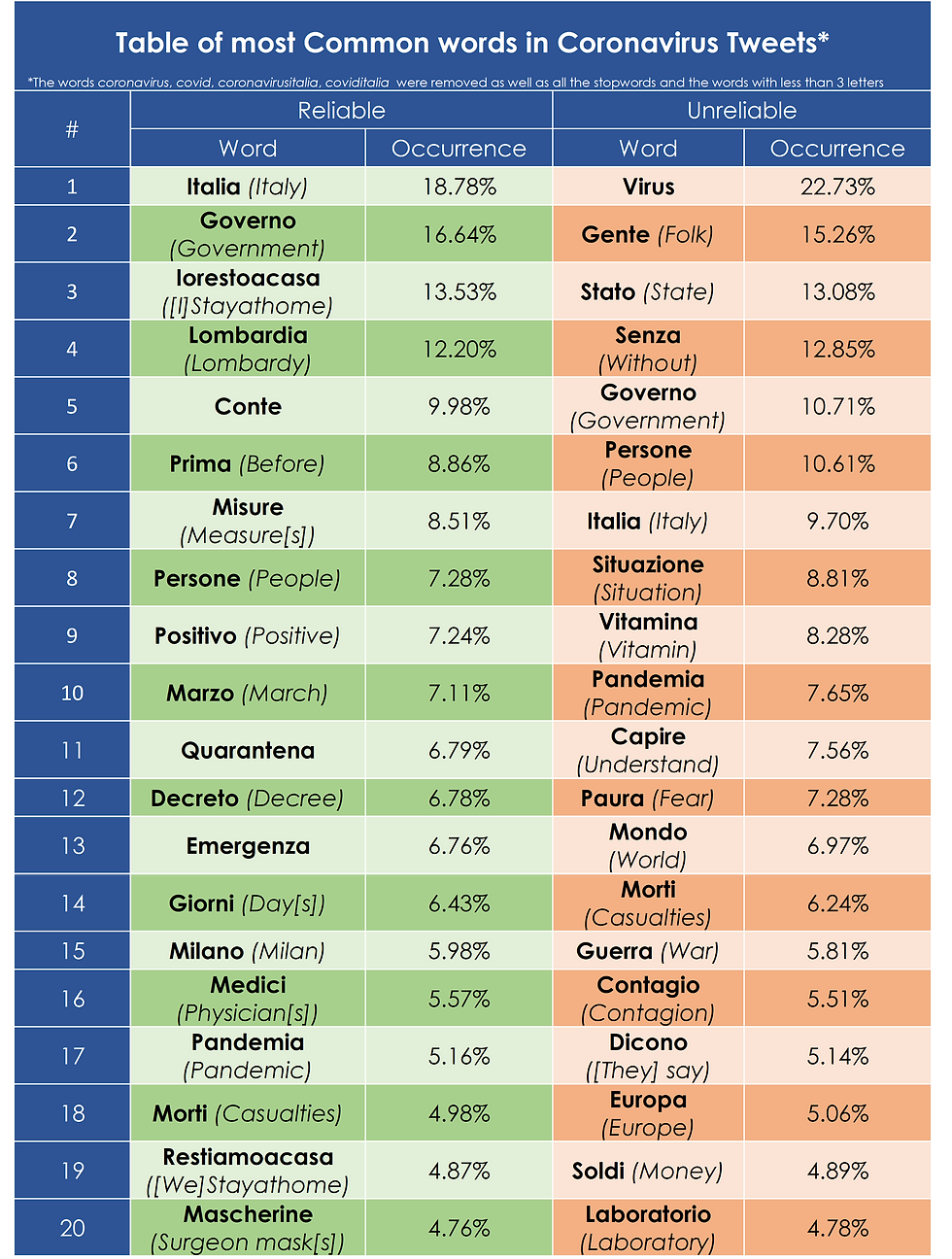

Some interesting insights may be extracted from the vocabulary used in the tweets. In the following table, the 20 most common words in reliable and unreliable tweets are shown. The occurrence frequency is shown in relative terms rather than absolute ones as the sample sizes of the two groups are drastically different (the vast majority of distinct tweets are reliable).

At first glance, the words present in both lists pertain to the socio-political semantic field (Italia, Governo, Persone; transl. Italy, Government, People) and to the epidemiological one (Pandemia, Morti; transl. Pandemic, Casualties).

Looking at the differences, the reliable tweets exhibit a high occurrence of the hashtags #iostoacasa and #restiamoacasa (transl. #stayathome) referring to the Italian social movement. In contrast, in the unreliable tweets, such hashtags appeared respectively in the 367th and 1349th position. Common words in reliable tweets seem to refer to a specific scope in terms of geography (transl. Lombardy, Milan – the Italian region most affected by the virus), politics (Misure, Conte, Decreto; transl. Measures, Conte, Decree – respectively referring to political measures, the Italian prime minister and the Italian decree of 10th March) and epidemiology (Positivo [al COVID-19], Quarantena, Medici; transl. Positive [for COVID-19], Quarantine, Physicians).

On the other hand, the words used in unreliable tweets seem to refer to broader concepts, both geographically (Stato, Mondo, Europa; transl. State, World, Europe) and socially (Gente; transl. Folk – Gente slightly differs from Persone as it aggregates the individuals in a very generic way implying a loss of their specific qualities). Vitamina and Laboratorio (transl. Vitamin and Laboratory) presumably refers to the fake news circulating about the beneficial effects of vitamin C and D against the virus and the conspiracy theory that the virus was created in a lab. Furthermore, Guerra and Soldi (transl. War and Money) appearance is quite interesting since the respective semantic fields are not commonly correlated with the pandemic (indeed, the former could be a reference to the Spanish flu during World War I, but the fact that this term comes up in more than 1 in every 20 unreliable tweets gives rise to some suspicion). Finally, the appearance of the term Capire (transl. Understand), which falls into the semantic field of knowledge and learning, is a quite paradoxical association for tweets that have been labelled as unreliable.

In short, unreliable tweets seem to generalize while reliable tweets refer to specific events and policies; furthermore, unreliable tweets rely on triggering the attention of the readers with catchy phrases related to knowledge (“you should know that…” or “why people don’t understand that...”) and evoke concepts and topics that are hardly factual or related to COVID-19.

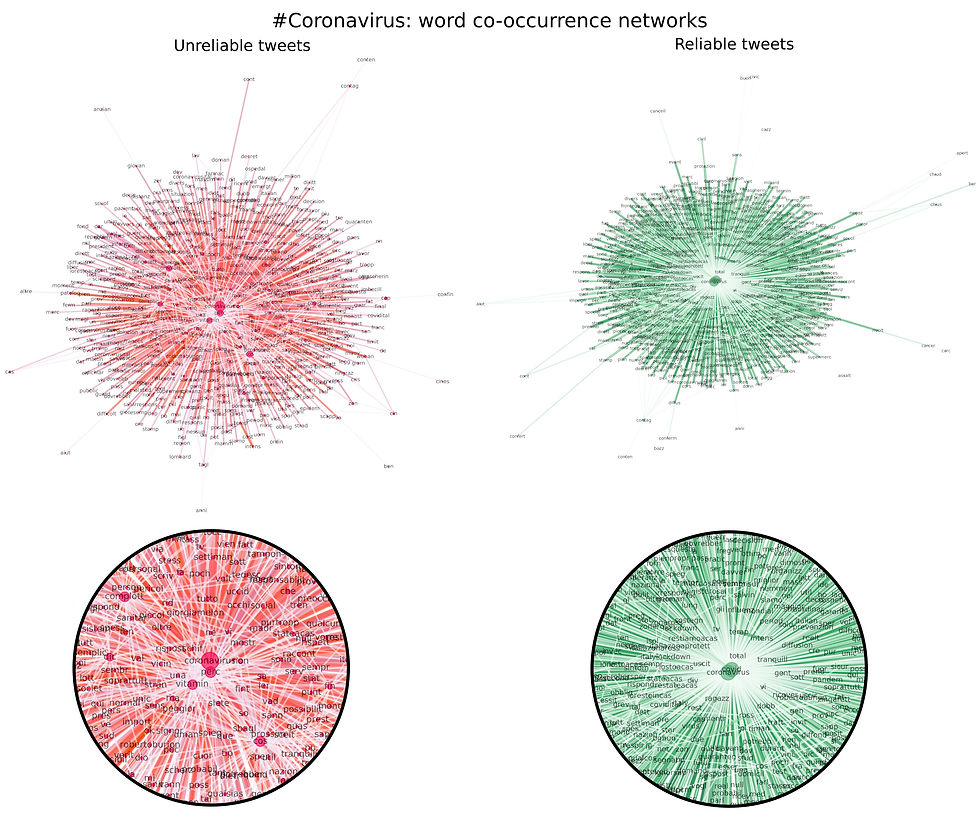

A final step consists in analysing the relationship among the words discussed above, and this can be done by analysing the co-occurrence networks of the two subsamples which will from now on be called the reliable network and unreliable network.

Networks are composed of nodes linked by edges. Each node represents what is called a stem, namely the root of a group of words (e.g. comput- is the stem of the words computer and computation); this operation is extremely important in languages such as Italian where conjugation produces many variations for terms expressing the same concept. The nodes are linked by edges of different intensities depending on how many times the two terms appear together in a tweet; the edges’ magnitude is expressed by their width and their color. Finally, the centrality of the node expresses the number of connections it has, namely, with how many words it appears together; graphically, it is represented by the size of the node and by how central the node is in the network. Minimum thresholds, both in terms of centrality of the node and in terms of intensity of the relationship between words, were set in order to simplify the networks.

Comparing the two graphs, it appears that more words are clustered around the centre in the unreliable network, while the reliable system exhibits a more hierarchical structure where covid-19 and coronavirus are linked to other words which in turn are forming their own clusters. In this sense, the most interesting central words in the unreliable network, beside the obvious coronavirus and covid-19 (the search terms for the dataset) are complot- and vitamin- (respectively the stems of the Italian words for conspiracy and vitamin), while in the reliable network cas-, iorestoacas- and itali- (respectively stemming home, stayathome, Italy) play a central role.

The unreliable network shows fewer words than the reliable one, despite the applied thresholds being identical; moreover, the words in the unreliable networks appear to be more interconnected. In general, the strongest connections are obviously those with coronavirus and covid-19 in both graphs, although some pairs of words that tended to appear together more frequently (zon- & ross-, terap- & intens-; the former referring to the red zone, the area restricted due to the contagion, the latter to the intensive unit care). In particular, intensive units appeared to show a high centrality in the reliable network.

Since unreliable tweets showed higher density around the term coronavirus and the terms used were highly interconnected, this means that the unreliable tweets tend to use similar terms and to pair them together more frequently. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that unreliable tweets tend to refer to a limited number of fake news (e.g. vitamin C, conspiracy theory) that are nevertheless massively diffused. In contrast, reliable tweets are more wordy, less densely aggregated around the center, with lower levels of connectivity; it is possible to infer that reliable tweets discuss more aspects of the crisis.

Conclusion

Finally, we can wrap up the analysis by looking at the following main insights:

Considering only original tweets, one tweet out of ten was classified as unreliable.

Including also retweets, one tweet out of four was classified as unreliable.

Half of the unreliable tweets were propagating misinformative fake news, while one quarter were a clickbait and only a small part was related to conspiracy.

The vocabulary used in unreliable tweets seems more general, more uniform, more repetitive and less related specifically to the virus; unreliable tweets show a high level of interconnection among multiple words.

The vocabulary used in reliable tweets seems to be more specific, both in terms of lexicon used and its relationship with COVID-19; furthermore, the words show low levels of interconnection, due to a more diversified and less centralized vocabulary.